by Thomas Zei

The Incident at the Inn in Triune

After delaying joining his troops as they pursued General Hood’s retreat from Nashville, Captain Charles G. Penfield rode his horse trying to locate the 44th USCT Infantry Regiment. He was joined on his ride by Lt. George Fitch, Quartermaster of the 12th USCT, Lt. David Grant Cooke, also of the 12th USCT, and two other officers. They left Nashville on December 20, 1864 traveling south on the Nolensville Pike. When they reached the small crossroads of Triune where the road to Murfreesboro and Franklin crossed the Nolensville Pike, they noticed a local inn.

Penfield, Fitch and Cooke wanted to eat a meal at the inn. The two other officers advised them strongly that they needed to move on. These two officers knew the area was still an area of Confederate activity and the officers still needed the time to catch up to their units before the early winter night. Despite the advice, the three officers decided to stay behind at the inn for food and rest.

The inn was soon surrounded by about 36 scouts from General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s forces under the command of Captain Addison Harvey. Penfield, Fitch and Cooke were stripped of their clothing and valuables. They were joined by a group of other soldiers from USCT units and forced to march to the south. On December 22nd, they reached the area near Lewisburg where the three officers were separated from the larger group and were led away by four members of Harvey’s unit. They were told that they were being taken to General Forrest’s headquarters. They were on a road leading from Lewisburg to Mooresville when they veered off to a side road. The men told the officers that they were going to a house to spend the night. A short distance down the road, one of the horsemen turned towards the officers shooting each one in the head.

Surprisingly, Lt. Fitch was able to later tell the story of what happened on that road. He wrote on January 3, 1865:

After delaying joining his troops as they pursued General Hood’s retreat from Nashville, Captain Charles G. Penfield rode his horse trying to locate the 44th USCT Infantry Regiment. He was joined on his ride by Lt. George Fitch, Quartermaster of the 12th USCT, Lt. David Grant Cooke, also of the 12th USCT, and two other officers. They left Nashville on December 20, 1864 traveling south on the Nolensville Pike. When they reached the small crossroads of Triune where the road to Murfreesboro and Franklin crossed the Nolensville Pike, they noticed a local inn.

Penfield, Fitch and Cooke wanted to eat a meal at the inn. The two other officers advised them strongly that they needed to move on. These two officers knew the area was still an area of Confederate activity and the officers still needed the time to catch up to their units before the early winter night. Despite the advice, the three officers decided to stay behind at the inn for food and rest.

The inn was soon surrounded by about 36 scouts from General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s forces under the command of Captain Addison Harvey. Penfield, Fitch and Cooke were stripped of their clothing and valuables. They were joined by a group of other soldiers from USCT units and forced to march to the south. On December 22nd, they reached the area near Lewisburg where the three officers were separated from the larger group and were led away by four members of Harvey’s unit. They were told that they were being taken to General Forrest’s headquarters. They were on a road leading from Lewisburg to Mooresville when they veered off to a side road. The men told the officers that they were going to a house to spend the night. A short distance down the road, one of the horsemen turned towards the officers shooting each one in the head.

Surprisingly, Lt. Fitch was able to later tell the story of what happened on that road. He wrote on January 3, 1865:

|

|

“The ball (from the revolver) entered my right ear just above the center passed through and lodged in the bone back of the ear. It knocked me senseless for a few moments. I soon recovered however but lay perfectly quiet, knowing that my only hope lay in leading them to believe that they had killed me. Presently I heard two carbine shots and then all was still. After about fifteen minutes I staggered to my feet and attempted to get away but found I could not walk. About that time a colored boy came along and helped me to a house nearby. He told me the other two officers were dead, having been shot in the head.

That evening their bodies were brought to the house where I lay. Next morning they were decently buried on the premises of Col. Jno C Hill nearby. The shoot occurred on the 22nd and on the 23rd about midday one of Forrest’s men came to the house where I was lying and enquired for me, said he had come by to kill me. The man of the house said that it was unnecessary, as I was so severely wounded that I would die anyway and he expected I would not live more than an hour. He then went away saying that if I was not dead by morning that I would be killed. After he left, I was moved by the neighbors to another house and was moved nearly every night from the house to another until the 27th when I was retrieved by a party of troops sent from Columbia and brought within the federal lines. The privates were sent off on a road leading to the right of the one we took in the direction of Columbia I should judge. I cannot but think they were killed as about that time our forces occupied Columbia the rebel army having retreated. There were 12 Privates belonging, I think to Cruft’s Brigade.” |

The murders greatly angered the Union command. General George Thomas personally wrote a letter to General Hood on January 13, 1865 advising him of the facts and warned that if the murders did not stop, he anticipated his officers would take similar treatment of Confederate prisoners of war. Even General Grant wrote a similar letter to General Lee on March 11, 1865 asking Lee to issue orders to his officers to stop such practices.

The Confederates, though, were operating under policies issued by Lee in December, 1862 that allowed execution of White officers commanding former slaves. The former slaves would be sent back to the states they came from and distributed to the slave owners. This policy was later modified by the Confederate Congress on May 30, 1863 that required officers commanding Black units be tried under military courts and punished. The actions by Harvey’s troops did not follow this modified policy.

After Lt. Fitch recovered from his head wound, he was well enough to return to his unit where he later was promoted to captain.

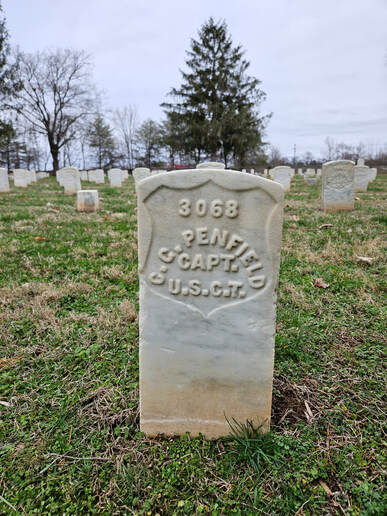

The bodies of Captain Penfield and Lieutenant Cooke were retrieved in 1865. Cooke’s remains were transported to Dubuque, Iowa where he was buried. Penfield was buried with other Union soldiers at Rose Hill Cemetery in Columbia, TN. When the decision was made to move all the Union soldiers out of Rose Hill and rebury them in the Stones River National Cemetery, Penfield was placed in Section H, Grave 3068.

The Confederates, though, were operating under policies issued by Lee in December, 1862 that allowed execution of White officers commanding former slaves. The former slaves would be sent back to the states they came from and distributed to the slave owners. This policy was later modified by the Confederate Congress on May 30, 1863 that required officers commanding Black units be tried under military courts and punished. The actions by Harvey’s troops did not follow this modified policy.

After Lt. Fitch recovered from his head wound, he was well enough to return to his unit where he later was promoted to captain.

The bodies of Captain Penfield and Lieutenant Cooke were retrieved in 1865. Cooke’s remains were transported to Dubuque, Iowa where he was buried. Penfield was buried with other Union soldiers at Rose Hill Cemetery in Columbia, TN. When the decision was made to move all the Union soldiers out of Rose Hill and rebury them in the Stones River National Cemetery, Penfield was placed in Section H, Grave 3068.

Coincidentally, Penfield was buried next to Lt. Col JD Elliott. Elliott in September, 1864 surrendered his troops in Tanner, Alabama to a unit of General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s forces. Within Elliott’s two regiments was the Michigan 18th Infantry Regiment, the very unit Penfield mustered out to join the 44th USCT Regiment. Elliott’s forces were captured by forces led by General Warren [there is no record of a General Warren as a Confederate general.] Warren then shoots Elliott in the head in front of all his surrendered troops. Elliott is mortally wounded and dies a month later while being cared for by a local resident. Elliott did not command any USCT soldiers so his killing seems totally unjustifiable.

These are two executions of captured officers by troops under the command of General Forrest. Both had a connection to the 18th Michigan Regiment. Both were shot in the head. They may have had different size headstones but they certainly had much in common in their tragic endings.

Were both actions an act of war? Was it murder? Was it acceptable under CSA laws? What happened to the other two unnamed companions traveling down Nolensville Pike and did their decision to go on lead to a different fate? Or were they too captured?