Every visitor that walks through Stones River National Battlefield’s Museum passes a large drawing on the wall but few actually stop to look at it. Despite the prominent position in the museum, the visitors are focused on finding the turn to get to the theatre and then retracing their steps to continue their tour through history. But if they took the time to look at the large drawing, they would probably turn their heads away from the shocking and graphic display. For the drawing displays the last moment of Lt. Colonel Julius Gareschè’s life.

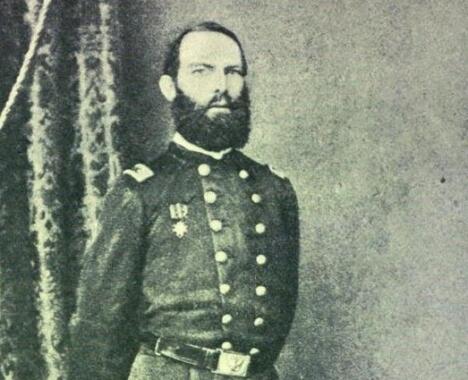

Julio Pedro Gareschè (“GA-ra-shay”) de Rocher was born on April 26, 1821 in Havana, Cuba. His father was a descendent of French Huguenots who were forced to flee France due to their religion. Julio moved around the Caribbean and the United States as his father had many business interests. While in the U.S., he Americanized his name to Julius Peter Gareschè. Starting in 1833, he attended school for four years in Georgetown in Washington. By 1837, he obtained an appointment to West Point where he graduated with a second lieutenant commission in 1841.

While at West Point, Gareschè received many demerits for his conduct. He also suffered from severe nearsightedness and illness, all of which impacted his class standing. He did become great friends with a cadet in a class behind him. This cadet, William Rosecrans, became enthralled with the great religious belief of Julius and they had long discussions about religion. Eventually, Rosecrans became a Roman Catholic like his best friend.

Gareschè’s Catholic faith led him to a dedication to helping the poor in the cities where he was assigned. He became actively involved in the St Vincent de Paul Society which provided food and services in Newark, NJ. Later, he created a chapter of the organization in Washington, D.C.

Throughout his adult life, Gareschè had several near-death experiences. His brother, a Catholic priest, convinced him that each event was an omen that Julius would suffer a violent death. During the early days of the Civil War, Gareschè’s brother told him that Julius would be killed in his first battle, and that it would happen within the next eighteen months.

Although he was a career officer, he had little field experience having risen through the ranks in headquarters staff positions. Despite his brother’s “vision”, Gareschè began taking steps to obtain a position with an active army. His opportunity came when his dear friend William Rosecrans was appointed commander of the Union forces that would eventually be called the Army of the Cumberland. On November 5, 1862, he received an appointment as Rosecrans’ Chief-of-Staff. His position utilized his writing skills preparing reports and issuing orders to the command staff. It also allowed him to become the close confidant to General Rosecrans where they discussed tactics and religion.

Artillery in the Civil War

Before proceeding, we need to briefly discuss artillery in the Civil War. Most people think that cannons only fired solid round cannonballs. In reality, solid cannonballs were only used for punching holes in ships and structures. Solid balls were not very effective when firing at troops since the only ones injured were those in the direct line of fire.

Rather than solid cannonballs firing at infantry, hollowed out shells were used. These were then filled with various sized metal balls and explosive. A secondary fuse on the top of the shell led down a hole to the explosive inside. As the shell exited out the cannon through the flaming exhaust, the fuse would light. The rifling of the cannon barrel kept the shell heading in the aimed course until the secondary explosion occurred raining shrapnel over the troops causing many injuries and death. Artillery was mostly likely the leading cause of casualties, especially for the Confederate forces.

The armament factories in the North were very good at making shells and the fuses. The result of the manufacturers’ design and quality control resulted in shells that exploded almost all the time as scheduled. Factories in the South used a different fuse design that didn’t always explode as it travelled through the air to its target. Some of the fuses never lit or burned too slowly to be effective.

At the Battle of Stones River, Confederate forces also faced shortages in artillery shells. This shortage resulted in rationing of ammunition for the cannons.

For a full discussion on the use of artillery during the battle, make sure to come to any of the living history cannon demonstrations. Check the park’s social media pages for scheduled dates and times.

The Premonition Comes True

Fifteen months after his brother’s premonition, Gareschè and Rosecrans marched toward Murfreesboro at the end of December, 1862. The Union’s plan for beginning the battle with the Left Flank crossing the Stones River at McFadden’s Ford was quickly halted once General Rosecrans finally heard mid-morning about the crushing rout by the Confederates on the Union Right. Rosecrans knew that he had to redeploy his troops to positions that would protect his only means of escape and resupply via the Nashville Pike and the railroad.

General Rosecrans was a very hands-on commander who did not like staying in his headquarters far from the action. He wanted to see for himself the battlefield and he personally wanted to rally his troops. Old “Rosey” was much beloved by his troops for his continued moral support and encouragement during the fight. It also brought him closer to danger out in the open.

Rosecrans was assigned the services of the Pennsylvania Cavalry Anderson Troop led by Lt. Thomas Maple as an escort. The Ohio 10th Infantry Regiment was also assigned as his provost guard for further protection. As he surveyed the battle on his horse, it brought him to the area on the north side of the railroad, somewhere between the present-day national cemetery and the area known as the Round Forest. He was accompanied by his Chief of Staff Gareschè, other staff members and the PA Cavalry unit.

The large group of soldiers on horseback became visible to the group of Confederate artillery men stationed on the rise that became known as Wayne’s Hill, a little less than a mile away. A group of soldiers on horseback either meant a cavalry unit or a meeting of officers. Considering it was in the middle of the battlefield, it was more likely to be a meeting of officers. The artillery men were given permission to fire one shell at the target from their rationed arsenal. The unit carefully aimed and fired. The remaining questions would be whether they fired accurately from almost a mile away and whether the fuse in the shell would explode mid-flight.

At this moment, Rosecrans and his fellow horsemen began riding in the direction of the Round Forest. The sound of the approaching cannon shell was probably masked by the noise of the on-going battle. As the horsemen rode, the shell arrived at the moving target in tact. It did not explode. Instead, the shell became the same as a solid cannonball. Directly in line with the shell was the head of Lt. Col. Julius Gareschè.

Gareschè was decapitated at the neck from the shell. The shell continued on its course hitting the horse and rider of the unfortunate escort riding behind Gareschè. Rosecrans was splattered with remnants of his friend’s head showing how close he was to Gareschè’s position. As he slowly cleaned his uniform, Rosecrans reportedly said “In war, good men die”. Reports indicated that after the impact, Gareschè’s horse continued forward for 200 yards with his body still on the horse leading to stories about a headless horseman at the Battle of Stones River.

Colonel William Hazen would supposedly later direct the burial of Gareschè’s body after nightfall. A pencil drawing of the burial is in the National Archives. The next day, the body was then taken to Nashville and later shipped to Washington for burial at Mount Olivet Cemetery. It is questionable why the body was buried by Hazen instead of just adding it to the large caravan of wagons carrying the wounded back to Nashville, especially considering the importance of the soldier. If they were burying it near where he fell, why did they wait until dark? Did they really leave a prominent body just laying around on a battlefield from the late morning?

After the battle, the position of Chief of Staff for Rosecrans was later filled by James Garfield of Ohio, who became the 20th President of the United States.

What If the Shell Exploded?

Although the cannon shell resulted in the death of a key advisor and close friend of General Rosecrans, the question rises as to the potential impact if the shell’s fuse had exploded as it was designed.

Due to the close positioning of Rosecrans to Gareschè, it is very likely that he would have been seriously wounded or killed if the shell rained shrapnel. At the very least, his wounds would remove him from commanding the Union troops.

Official reports do not indicate which other officers of the command staff were present at the time of the incident. There are reports that indicate corps commanders George Thomas and Thomas Crittenden were with Rosecrans along with their staffs. Although not shown in the official reports, the timing of the meeting when Rosecrans was trying to formulate plans to reposition his troops after the collapse of the Union Right Flank could support the need to have his commanding officers of the Center and Left Flanks there as he viewed the battlefield.

Some suggest that General Phillip Sheridan was also present at the meeting and that he came across the body shortly after the incident. If the incident occurred approximately at 10:45AM, Sheridan probably was still overseeing the withdrawal of his troops from the area of the Slaughter Pen as he fulfilled Rosecrans’ request to hold the line for two hours while Rosecrans re-positioned his troops.

There is also a report that Major General Lovell Rousseau was also nearby, close enough to take an order from Rosecrans that he must hold the Round Forest area.

Just losing the Union’s commanding officer would have significant impact on the result of the battle. Not only losing the key decision maker, troop supporter and tactician, Rosecrans was also the driving force behind the decision to not retreat from the battlefield at the end of December 31, 1862. But the possible addition of losing Generals Thomas and Crittenden would have placed command into the hands of the largely incompetent General Alexander McCook, commander of the corps on the Union Right Flank.

Gareschè Impact at the National Battlefield

Julius Gareschè is one the few Hispanics who fought in the Civil War and certainly one of the highest ranked Hispanics. His story is important to tell for the Spanish-American community. He is also highly respected with the Roman Catholic community for his work with the poor and promoting his faith. He also has a following for the premonition that he would die in his first battle. As a result, people will make "pilgrimages" just to see the site where Gareschè died.

One of the few markers on the battlefield is devoted to the death of Gareschè. It is in a location not easily found by the casual visitor. The marker sits along the old remnants of Van Cleve (or McFadden) Lane where it nears the old railroad crossing on the west side of the Round Forest. It can be reached from Tour Stop Five taking a trail that winds through the Round Forest.

After a long period of heavy rain, water will start pooling in the Cotton Field area on the south side of Old Nashville Highway. This pool can be quite large and remains for a long time as the water drains out through the cedar woods south of the visitor center. The water comes from the cemetery area and probably also from sink holes connecting to the distant river area. The pond when it exists is called Lake Gareschè by the park staff due to its proximity to his death location.

The most prominent tribute to Julius Gareschè is the large drawing showing the moment of his demise. Only a small sign to the left of the drawing explains the meaning but it is easily missed in the darkness and height of the note. Although gruesome, it is a tribute to an important part of the Stones River story and possible consequences if the shell had exploded as intended.

- by Thomas Zei

Julio Pedro Gareschè (“GA-ra-shay”) de Rocher was born on April 26, 1821 in Havana, Cuba. His father was a descendent of French Huguenots who were forced to flee France due to their religion. Julio moved around the Caribbean and the United States as his father had many business interests. While in the U.S., he Americanized his name to Julius Peter Gareschè. Starting in 1833, he attended school for four years in Georgetown in Washington. By 1837, he obtained an appointment to West Point where he graduated with a second lieutenant commission in 1841.

While at West Point, Gareschè received many demerits for his conduct. He also suffered from severe nearsightedness and illness, all of which impacted his class standing. He did become great friends with a cadet in a class behind him. This cadet, William Rosecrans, became enthralled with the great religious belief of Julius and they had long discussions about religion. Eventually, Rosecrans became a Roman Catholic like his best friend.

Gareschè’s Catholic faith led him to a dedication to helping the poor in the cities where he was assigned. He became actively involved in the St Vincent de Paul Society which provided food and services in Newark, NJ. Later, he created a chapter of the organization in Washington, D.C.

Throughout his adult life, Gareschè had several near-death experiences. His brother, a Catholic priest, convinced him that each event was an omen that Julius would suffer a violent death. During the early days of the Civil War, Gareschè’s brother told him that Julius would be killed in his first battle, and that it would happen within the next eighteen months.

Although he was a career officer, he had little field experience having risen through the ranks in headquarters staff positions. Despite his brother’s “vision”, Gareschè began taking steps to obtain a position with an active army. His opportunity came when his dear friend William Rosecrans was appointed commander of the Union forces that would eventually be called the Army of the Cumberland. On November 5, 1862, he received an appointment as Rosecrans’ Chief-of-Staff. His position utilized his writing skills preparing reports and issuing orders to the command staff. It also allowed him to become the close confidant to General Rosecrans where they discussed tactics and religion.

Artillery in the Civil War

Before proceeding, we need to briefly discuss artillery in the Civil War. Most people think that cannons only fired solid round cannonballs. In reality, solid cannonballs were only used for punching holes in ships and structures. Solid balls were not very effective when firing at troops since the only ones injured were those in the direct line of fire.

Rather than solid cannonballs firing at infantry, hollowed out shells were used. These were then filled with various sized metal balls and explosive. A secondary fuse on the top of the shell led down a hole to the explosive inside. As the shell exited out the cannon through the flaming exhaust, the fuse would light. The rifling of the cannon barrel kept the shell heading in the aimed course until the secondary explosion occurred raining shrapnel over the troops causing many injuries and death. Artillery was mostly likely the leading cause of casualties, especially for the Confederate forces.

The armament factories in the North were very good at making shells and the fuses. The result of the manufacturers’ design and quality control resulted in shells that exploded almost all the time as scheduled. Factories in the South used a different fuse design that didn’t always explode as it travelled through the air to its target. Some of the fuses never lit or burned too slowly to be effective.

At the Battle of Stones River, Confederate forces also faced shortages in artillery shells. This shortage resulted in rationing of ammunition for the cannons.

For a full discussion on the use of artillery during the battle, make sure to come to any of the living history cannon demonstrations. Check the park’s social media pages for scheduled dates and times.

The Premonition Comes True

Fifteen months after his brother’s premonition, Gareschè and Rosecrans marched toward Murfreesboro at the end of December, 1862. The Union’s plan for beginning the battle with the Left Flank crossing the Stones River at McFadden’s Ford was quickly halted once General Rosecrans finally heard mid-morning about the crushing rout by the Confederates on the Union Right. Rosecrans knew that he had to redeploy his troops to positions that would protect his only means of escape and resupply via the Nashville Pike and the railroad.

General Rosecrans was a very hands-on commander who did not like staying in his headquarters far from the action. He wanted to see for himself the battlefield and he personally wanted to rally his troops. Old “Rosey” was much beloved by his troops for his continued moral support and encouragement during the fight. It also brought him closer to danger out in the open.

Rosecrans was assigned the services of the Pennsylvania Cavalry Anderson Troop led by Lt. Thomas Maple as an escort. The Ohio 10th Infantry Regiment was also assigned as his provost guard for further protection. As he surveyed the battle on his horse, it brought him to the area on the north side of the railroad, somewhere between the present-day national cemetery and the area known as the Round Forest. He was accompanied by his Chief of Staff Gareschè, other staff members and the PA Cavalry unit.

The large group of soldiers on horseback became visible to the group of Confederate artillery men stationed on the rise that became known as Wayne’s Hill, a little less than a mile away. A group of soldiers on horseback either meant a cavalry unit or a meeting of officers. Considering it was in the middle of the battlefield, it was more likely to be a meeting of officers. The artillery men were given permission to fire one shell at the target from their rationed arsenal. The unit carefully aimed and fired. The remaining questions would be whether they fired accurately from almost a mile away and whether the fuse in the shell would explode mid-flight.

At this moment, Rosecrans and his fellow horsemen began riding in the direction of the Round Forest. The sound of the approaching cannon shell was probably masked by the noise of the on-going battle. As the horsemen rode, the shell arrived at the moving target in tact. It did not explode. Instead, the shell became the same as a solid cannonball. Directly in line with the shell was the head of Lt. Col. Julius Gareschè.

Gareschè was decapitated at the neck from the shell. The shell continued on its course hitting the horse and rider of the unfortunate escort riding behind Gareschè. Rosecrans was splattered with remnants of his friend’s head showing how close he was to Gareschè’s position. As he slowly cleaned his uniform, Rosecrans reportedly said “In war, good men die”. Reports indicated that after the impact, Gareschè’s horse continued forward for 200 yards with his body still on the horse leading to stories about a headless horseman at the Battle of Stones River.

Colonel William Hazen would supposedly later direct the burial of Gareschè’s body after nightfall. A pencil drawing of the burial is in the National Archives. The next day, the body was then taken to Nashville and later shipped to Washington for burial at Mount Olivet Cemetery. It is questionable why the body was buried by Hazen instead of just adding it to the large caravan of wagons carrying the wounded back to Nashville, especially considering the importance of the soldier. If they were burying it near where he fell, why did they wait until dark? Did they really leave a prominent body just laying around on a battlefield from the late morning?

After the battle, the position of Chief of Staff for Rosecrans was later filled by James Garfield of Ohio, who became the 20th President of the United States.

What If the Shell Exploded?

Although the cannon shell resulted in the death of a key advisor and close friend of General Rosecrans, the question rises as to the potential impact if the shell’s fuse had exploded as it was designed.

Due to the close positioning of Rosecrans to Gareschè, it is very likely that he would have been seriously wounded or killed if the shell rained shrapnel. At the very least, his wounds would remove him from commanding the Union troops.

Official reports do not indicate which other officers of the command staff were present at the time of the incident. There are reports that indicate corps commanders George Thomas and Thomas Crittenden were with Rosecrans along with their staffs. Although not shown in the official reports, the timing of the meeting when Rosecrans was trying to formulate plans to reposition his troops after the collapse of the Union Right Flank could support the need to have his commanding officers of the Center and Left Flanks there as he viewed the battlefield.

Some suggest that General Phillip Sheridan was also present at the meeting and that he came across the body shortly after the incident. If the incident occurred approximately at 10:45AM, Sheridan probably was still overseeing the withdrawal of his troops from the area of the Slaughter Pen as he fulfilled Rosecrans’ request to hold the line for two hours while Rosecrans re-positioned his troops.

There is also a report that Major General Lovell Rousseau was also nearby, close enough to take an order from Rosecrans that he must hold the Round Forest area.

Just losing the Union’s commanding officer would have significant impact on the result of the battle. Not only losing the key decision maker, troop supporter and tactician, Rosecrans was also the driving force behind the decision to not retreat from the battlefield at the end of December 31, 1862. But the possible addition of losing Generals Thomas and Crittenden would have placed command into the hands of the largely incompetent General Alexander McCook, commander of the corps on the Union Right Flank.

Gareschè Impact at the National Battlefield

Julius Gareschè is one the few Hispanics who fought in the Civil War and certainly one of the highest ranked Hispanics. His story is important to tell for the Spanish-American community. He is also highly respected with the Roman Catholic community for his work with the poor and promoting his faith. He also has a following for the premonition that he would die in his first battle. As a result, people will make "pilgrimages" just to see the site where Gareschè died.

One of the few markers on the battlefield is devoted to the death of Gareschè. It is in a location not easily found by the casual visitor. The marker sits along the old remnants of Van Cleve (or McFadden) Lane where it nears the old railroad crossing on the west side of the Round Forest. It can be reached from Tour Stop Five taking a trail that winds through the Round Forest.

After a long period of heavy rain, water will start pooling in the Cotton Field area on the south side of Old Nashville Highway. This pool can be quite large and remains for a long time as the water drains out through the cedar woods south of the visitor center. The water comes from the cemetery area and probably also from sink holes connecting to the distant river area. The pond when it exists is called Lake Gareschè by the park staff due to its proximity to his death location.

The most prominent tribute to Julius Gareschè is the large drawing showing the moment of his demise. Only a small sign to the left of the drawing explains the meaning but it is easily missed in the darkness and height of the note. Although gruesome, it is a tribute to an important part of the Stones River story and possible consequences if the shell had exploded as intended.

- by Thomas Zei